David Grann

Doubleday

“Nothing was more frequent than to bury eight or ten men from each ship every morning,” Millecamp wrote in his journal. Altogether, nearly 300 of the Centurion’s some 500 men were eventually listed as “DD”—Discharged Dead. Of the roughly 400 people on the Gloucester who had departed from England, three quarters were reported to have been buried at sea…Byron tried to offer his deceased companions a proper sea burial, but there were so many corpses, and so few hands to assist, that the bodies often had to be heaved overboard unceremoniously.

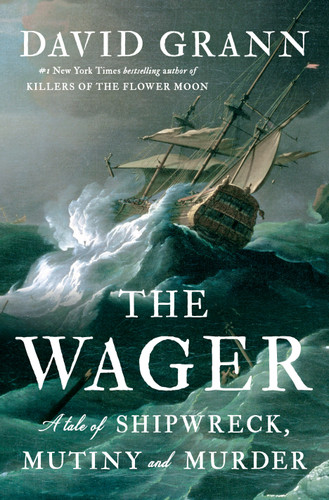

from The Wager

Reading with your heart in your throat

In January 1742, a leaky, patched-together vessel washed up onto Brazil’s coast. It contained 30 men so severely emaciated that the citizens of Rio Grande at first didn’t recognize them as human. The men were survivors of His Majesty’s Ship the Wager that had departed England one-and-one-half years earlier. Their ship, badly battered attempting the stormy Drake Passage around Cape Horn, had reached the Pacific, but then ran aground on an island off the coast of Patagonia in May 1741. Marooned and slowly starving on the desolate island, they had set out in October to make their way back around the horn of South America, traveling 3000 miles, this time in their flimsy, make-shift craft. It was an extraordinary tale of fortitude and endurance, and the men were hailed as heroes.

Then, six months later, another decrepit vessel landed on the coast of Chile. It held only three men, also from the Wager, but they told a very different tale. The thirty sailors were mutineers, guilty of the most abject treachery and murder. As the three castaways’ account became known, the first group responded with countercharges against the ship’s commanding officer whose incompetence and tyrannical personality had threatened to doom them all. The British Admiralty convened a court-martial to determine what really happened on that windswept island in the Gulfo de Penas, what the men had come to call the Gulf of Pain.

This is one of those books you read with your heart in your throat. David Grann (The Lost City of Z, Killers of the Flower Moon) writes history as if it were a novel—with breathtaking action, vivid characters, increasing suspense. He achieves this by drawing from the written accounts of key figures: David Cheap, captain of the Wager, lacking the respect of his men would rise above his shortcomings, displaying remarkable courage and determination in an extreme situation; the Wager’s gunner John Bulkeley, “an instinctive leader,” confident, resourceful, and able to command the respect and admiration from the crew, became leader of the mutineers; sixteen-year old John Byron, the younger son of a nobleman, had signed on as midshipman to make his own fortune in the world. The most attractive character in Grann’s telling, Byron becomes the conscience of the Wager, seeing the plight and desperation of the mutineers, yet remaining loyal to the captain in spite of Cheap’s failings. (He would survive the ordeal to become the grandfather of the poet Lord Byron.)

From their different accounts, Grann weaves the tale of the Wager, finally leaving the reader to weigh the merits of their actions—and too, to ponder what he or she would have done in such extreme situations.

This review first appeared in The Columbia River Reader (August 15, 2023.) Reprinted with permission.