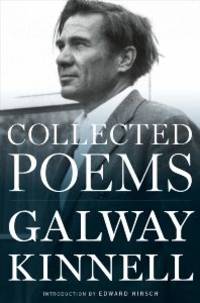

Galway Kinnell

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

|

Don’t know where to start? Here are some suggestions: Oregon poet William Stafford, or Billy Collins and Dorothy Parker for poetry seasoned with wry humor, Amanda Gorman, who wowed us at the inauguration, Bob Pyle’s Tidewater Reach, Gwendolyn Brooks (“We real cool.”) Edna St. Vincent Millay (she who burnt her candle at both ends), Adrienne Rich, current US poet laureate Joy Harjo, Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s classic Coney Island of the Mind, Mary Oliver, and (fill in the blank yourself.) Or try a smorgasbord of poets: Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry, or the Columbia Anthology of American Poetry.

|

Take a poet to bed during National Poetry Month

Poet Charles Bernstein once suggested that National Poetry Month’s motto should be “Poetry’s not so bad, really.”

Not exactly a ringing endorsement, but it’s true that for many of us poetry remains arcane and often inaccessible. I’m definitely not a poet; not even sure what makes a good poem. Many of the New Yorker poems leave me baffled—but then many of their cartoons leave me baffled as well.

Nonetheless, for National Poetry Month I decided to immerse myself in the poetry of one particular poet and picked up the collected poems of Galway Kinnell (1927-2014), resolving to read one or two each evening before falling asleep

I was drawn to Kinnell because of his nature poetry, not oohing and aahing over daffodils or sunsets, but his sensing a rough, vestigial identification with the natural world. Kinnell was, like Whitman, “mystically physical.”

My nightly experiment did not get off to a great start. His earlier poems left me cold and unmoved. Poem after poem, I’d shake my head, thinking “Haven’t a clue what he’s about.” (BUT on the positive side, they helped me fall asleep.) I found his poems deepened with meaning and became more accessible as he aged.

Poets play with language to say what hasn’t been said before, or at least not in this way. They use familiar words to help us see the world in unfamiliar ways: Listening to Pacific breakers—“The suck and inner boom/ As a wave tears free and crashes back/ In overlapping thunders.” Or in describing ice as “silenced water,” or “a woodpecker, double-knocking,” or lying next to one’s lover, “absorbing the astounding quantity of heat a slender body ovens up around itself.”

Sometimes the words are unfamiliar but perfect: “The sea scumbles in/ From its own inviolate border under the sky,” “a roof leak whucking into a pail.” Some poems resemble brief postcards: “Wilmington, Delaware, one of those American cities/ that start falling apart before they ever get finished.”

Through Kinnell’s poems we witness the poet maturing. He takes note of the fact that he is aging—“Here come the joggers./ I am sixty-one. The joggers are approximately very young.” He notes the other “rickety, well wattled old timers,” and that “the arthritic opposable thumb no longer opposes.”

These later poems reflect a seasoning that only comes with age: “Nobody likes to die/ But an old man/ Can know/ A gratefulness/ Toward time that kills him,/ Everything he loved was made of it.”

He finds himself approaching the end—“sick to stay, longing to come up against the ends of the earth, and climb over”—and finally intuits a strange peace and oneness with the world one has been born into: “Can you bless, or not curse,/ everything that struggles to stay alive/ on this planet of struggles?”

Not so bad, really.

This review first appeared in The Columbia River Reader (April 15, 2021.) Reprinted with permission.