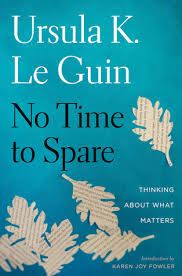

Ursula K. Le Guin

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

|

Because competition for primacy, for literary supremacy, doesn’t seem as glamorously possible for women as it does for men, the whole idea of singular greatness—of there being one great anything—may not have the hold on a woman’s imagination that it has on a man’s…The hell with The Great American Novel. We have all the great novels we need right now—and right now some man or woman is writing a new one we won’t know we needed till we read it. from No Time to Spare |

How do you spend your spare time?

Ursula K. Le Guin, beloved author of The Left Hand of Darkness, the Earthsea fantasy series and numerous other books, was one of our most influential writers of science and speculative fiction. Along with her novels, she also wrote poetry, essays, children’s literature, and, since 2010, blogs. No Time to Spare is a collection of her online writings.

She begins pondering a questionnaire from Harvard, which asks, In your spare time, what do you do?—“What is Harvard thinking of? I am going to be eighty-one next week. I have no time to spare.”

Writing from her “crabby old age,” she takes on a number of subjects, including aging. In these blogs, she is not ashamed to reveal her humanity in all its final frailty, vulnerability, and uncertainty, illuminated with occasional grace notes of wisdom that also come with age: “My fears come down to fear of not being safe (as if anyone is ever safe) and of not being in control (as if I ever was in control).”

There are a number of posts about her independently-minded cat, Pard (“If I wanted to be the center of the universe I’d have a dog.”) She shares her frustration with readers who write, Please tell me the meaning of this book—“But that’s not my job, honey. That’s your job. I know, at least in part, what my story means to me. It may well mean something quite different to you.” She is gentler in her responses to letters from children, though frustrated when the letter was clearly an assignment: “One desperate ten-year-old forced to write the author told me: ‘I have read the cover. It is prety good.’ What am I supposed to say to him?”

She ponders The Great American Novel, finding the whole idea rather silly. “I’ve never heard a woman writer say she intended, or wanted, to write the great American novel. Tell you true, I’ve never heard a woman writer say the phrase ‘the great American novel’ without a sort of snort.” It seems to be a guy thing.

A long time feminist, she argues for those qualities more typically found in the fellowship of women: “ad hoc rather than fixed, flexible rather than rigid, and more collaborative than competitive.” Pleased to see women making in-roads in a male-dominated world, she nonetheless wonders “Can women operate as women in a male institution without becoming imitation men?” Feisty, frustrated, impatient with injustice, she does not apologize for her anger. There’s just too darn much to be angry about!

Le Guin’s time finally ran out in January, but her voice will continue through her imaginative stories, through her poems and essays, and now through these last blogs.

This review first appeared in The Columbia River Reader (March 15-April 14, 2018.) Reprinted with permission.