Graeme Macrae Burnet

Skyhorse Publishing

|

“It is one of these things God sends to try us,” she said in a sing-song voice. I looked at her sideways. It was an oft-expressed sentiment in our parts. “I cannot imagine that God has no greater concerns than trying us,” I said. Flora looked at me quite earnestly. “Then why do such things happen?” she said. “What things?” I said. “Bad things.” “The minister would say that it is to punish us for wickedness,” I said. “And what would you say?” she asked. I hesitated a moment and then said, “I would say that they happen for no reason.” from His Bloody Project |

And he seemed like such a nice lad.

In August, 1869, a seventeen-year old youth commits a brutal triple murder in the Scottish farming community of Culdie.

The villagers have different and conflicting views of Roderick (Roddy) Macrae: his neighbor lady says he is invariably shy, kind and polite; his schoolmaster states he is the most gifted student he has ever taught; the parish minister declares he was wicked and damned long before the events of August 10th.

The boy’s advocate (attorney) Andrew Sinclair is ardent in his efforts to defend Roddy, arguing that it was an act of temporary insanity. But what accounts for insanity? Will he hang for the murders, and does he deserve to?

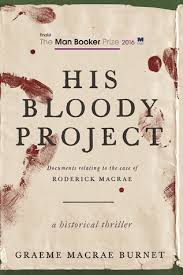

A finalist for the 2016 Man Booker Prize, His Bloody Project is only the second novel of Graeme Macrae Burnet, a Scottish writer, and proves that a gripping crime story can also be “literary fiction.”

Burnet tells his story through a collection of documents from the police investigation and subsequent trial, including Roddy’s psychological evaluation, statements from the villagers, medical reports of the victims, courtroom transcripts, and newspaper articles of the day. Central to understanding the youth is his written account of what happened. Yet aspects of the police’s investigation and the medical reports differ from that account.

Burnet transports the twenty-first century reader into the nineteenth century world with its very different understandings of family and blood kinship, of laws and justice, and of church and religion. Especially significant is the heavy predominance of fate, understood as God’s will, in the lives of the crofters (tenant farmers) eking out a living on the laird’s land and subject to the arbitrary authority of the shire’s constable.

In trying to understand the mystery of the human mind and the mix of personality and social environmental factors that could have produced such violent behavior, an expert psychiatrist—then called “alienists”—attempts to explain the boy’s actions through the science of “Criminal Anthropology” with its then current theories of criminal types and inherited criminal tendencies. Some of the alienist’s tools—for example, phrenology (studying the shape of the head to discern character and personality traits)—now seem closer to superstition than science.

Reading His Bloody Project, you can’t help but wonder what criminologists of the future will say about forensic psychiatry in the twenty-first century and our understanding of the “criminal mind.” Undoubtedly, they will have their own “theories”—yet will probably remain just as baffled about the complex, often contradictory yet coherent conundrum that is a human being.

This review first appeared in The Columbia River Reader (March 15, 2017-April 14, 2017.) Reprinted with permission.