Cheryl Strayed

Cheryl Strayed

Alfred A. Knopf

|

Uncertain as I was as I pushed forward, I felt right in my pushing, as if the effort itself meant something. That perhaps being midst the undesecrated beauty of the wilderness meant I too could be undesecrated, regardless of what I’d lost or what had been taken from me, regardless of the regrettable things I’d done to others or myself or the regrettable things that had been done to me. Of all the things I’d been skeptical about, I didn’t feel skeptical about this: the wilderness had a clarity that included me. from Wild |

Lessons learned on this journey called life

In 1995, 26-year old Cheryl Strayed’s life was coming apart at the seams. She was still experiencing the grief of her mother’s death four years earlier; she had sabotaged her marriage through multiple infidelities (“it’s all my fault…I’m the one. I broke my own heart”); and her use of alcohol and heroin wasn’t helping matters either.

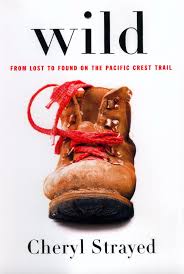

Sensing she needed to break out of the cycle of what her life had become, she decided she would walk the Pacific Crest Trail, or PCT to experienced backpackers, which she clearly was not. So she quit her waitress job in Minnesota, bought a backpack too large and boots too small, and set out on a three month, 1100 mile trek, starting in southern California and ending at the Bridge of the Gods on the Columbia.

Strayed, a Portland writer and author of the novel Torch, is wonderfully candid and confessional about her experience and her life leading up to it. As a young woman who obviously enjoyed sex, she brought along twelve condoms, and met a surprising number of men on the trail who she describes as “young” and “handsome,” suggesting either the degree of her luck or her desperation.

In addition to handsome, young men, she encounters a bull (“Moose!” I hollered) bears, rattlesnakes, and one very creepy Oregonian straight out of Deliverance, but with few other exceptions, she continually finds the kindness of strangers, fellow travelers on the PCT and this journey called life, who offer companionship, a cold beer, or the technical knowledge on backpacking that she woefully lacked.

One of them helps her reduce her overloaded backpack, which she nicknamed “Monster,” by discarding all non-essentials, including the twelve condoms. After a week on the trail, dirty, dusty, sweaty and smelly, she realizes, “I didn’t look like a woman who might need twelve condoms.”

It was a gutsy thing to do, and equally gutsy to write about it so candidly. The reader is less compelled to judge Strayed for the poor decisions she made in her twenties, than to recall one’s own poor decisions, and to admire her courage for confronting and changing the course of her life.

She notes, “I was amazed that what I needed to survive could be carried on my back. And, most surprising of all, that I could carry it.” One of many lessons she learned for all who travel this journey called life.

This review first appeared in The Columbia River Reader (July 15-August 14, 2015.) Reprinted with permission.