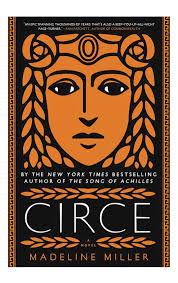

Madeline Miller

Little, Brown and Company

|

“War has always seemed to me a foolish choice for men. Whatever they win from it, they will have only a handful of years to enjoy before they die. More likely they will perish trying.” “Well, there is the matter of glory. But I wish you could’ve spoken to our general. You might have saved us all a lot of trouble.” “What was the fight over?” “Let me see if I can remember the list.” (Odysseus) ticked his fingers. “Vengeance. Lust. Hubris. Greed. Power. What have I forgotten? Ah, yes, vanity and pique.” “Sounds like a usual day among the gods.” from Circe |

Greek mythology for the #MeToo moment

-

You probably remember in The Odyssey that Circe was the sorceress who turned Odysseus’ men into pigs. Hearing Circe’s side of the story, as presented by Madeline Miller, they totally deserved it.

In The Song of Achilles (2012), Miller told the story of the Greek hero with the famous heel. In her new novel, she re-imagines parts of The Iliad and The Odyssey from a female perspective. The result is a tantalizing re-interpretation of these well-known stories.

Angering her father Zeus, Circe is exiled to live alone on an island. She wiles away the time by learning the arts of witchcraft. Since her parental time-out involves centuries, she gets very good at it.

In the course of Circe’s long banishment, Miller introduces familiar characters from Greek mythology: Jason and Medea, Daedulus and his high-flying son, Icarus, King Minos and the Minotaur. And of course, we meet Odysseus, aka Ulysses, if you prefer the Latin form of his name. (If you need to refresh your Greek mythology—Now, who was Telegonus again?—there is a handy reference at the back of the book with the names and descriptions of the various gods and goddesses, nymphs and naiads, titans, heroes and monsters.)

Miller has taken up the mantle of Mary Renault (The King Must Die, The Bull from the Sea) in giving ancient myths new life. Like Renault, she brings us into the living, breathing mythological world we first knew as children, where there are centaurs and giants, and where great passions rule both mortals and gods. She keeps faith with Homer’s original tale. Odysseus is still the wily charmer who can trick cyclops and seduce sorceresses (“Not even Odysseus could talk his way past witchcraft. He had talked his way past the witch instead.”) but he is also reckless, boisterous, egotistical, and seeks fame more than home. With his eventual return to Ithaca, we should not be surprised that his homecoming is brief and unhappy.

Circe will meet his grown son, Telemachus, who, raised by his mother, is very different from his legendary father—“He will be a good ruler, I thought. Fair-minded and warm. He will not be consumed like his father was. He had never been hungry for glory, only for life.”

The witchcraft that she practices is life-affirming and life-enhancing, close to nature, reflecting its ways and wisdom. However, when used aggressively, Circe learns that the results can be less than desirable. “The truth is,” she says, “men make terrible pigs.”

Plus, in the current #MeToo moment, turning men into pigs seems redundant.

This review first appeared in The Columbia River Reader (September 15-October 14, 2018.) Reprinted with permission.