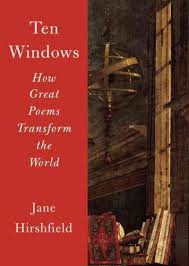

Jane Hirschfield

Jane Hirschfield

Alfred A Knopf

|

The desire of monks and mystics is not unlike that of artists: to perceive the extraordinary within the ordinary by changing not the world but the eyes that look. Within a summoned and hybrid awareness, the inner reaches out to transform the outer, and the outer reaches back to transform the one who sees. Catherine of Sienna wrote in the fourteenth century, “All the way to heaven is heaven”…to form the intention of new awareness is already to transform and be transformed. from Ten Windows: How Great Poems Transform the World. |

A poet's poetic musings on poetry

“Words transform,” declares poet Jane Hirschfield. As one who has spent much of his life interested in transforming the world—through the ministry, through community organizing and social services, and now through writing—I was intrigued by her subtitle: How Great Poems Transform the World.

I was thinking of the power of words in more concrete terms: Dickens’ novels resulting in the introduction of child labor laws, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin stirring outrage against slavery, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring awakening the environmental movement.

But Hirschfield is writing about transformation more subtle and more profound, transforming the world at the foundational level of perception rather than the political level of action, employing words and images instead of wars and revolutions. She is talking about “poems that leave us changed.”

She says, “What a writer or painter undertakes in each work of art is an experiment whose hoped-for outcome is an expanded knowing.” Through the expanded awareness that a poem can bring, we ourselves become expanded and something new; and as we are transformed, the world is also transformed.

These ten essays amount to a poet’s poetic musing on poetry, and she peppers the essays with poems that illustrate her points, those by canonical poets well known and much loved (Gerard Manley Hopkins, John Keats, Emily Dickinson), as well as by more contemporary poets (Denise Levertov, Gwendolyn Brooks, W.S. Merwin), but also by poets from other cultures who most of us probably do not know (the Iraqi poet Dunya Mikhail, the Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska.)

As one would expect of a poet, the essays are rich in metaphors—“A poem is a cup of words filled past its brim, carrying meanings beyond its own measurable capacity.”

Such poems “swerve into some new possibility of mind” and one suddenly sees the world in new ways—by “poem-light.”

What she is saying about poetry applies to all art: its innate capacity to transform the way we experience ourselves and the world. We are changed in the encounter, and then find that the world as we perceived it has also changed.

Through poems, she says, one can even “look into the unbearable,” and quotes a haiku by Issa:

We wander

the roof of hell,

choosing blossoms.

Hirschfield reminds us that this old, old world still has the potential to become new and fresh and original if we have the eyes, the will and (sometimes) the courage to see it.

This review first appeared in The Columbia River Reader (September 15-October 14, 2015.) Reprinted with permission.