November 2022 — A chat with Craig Allen Heath

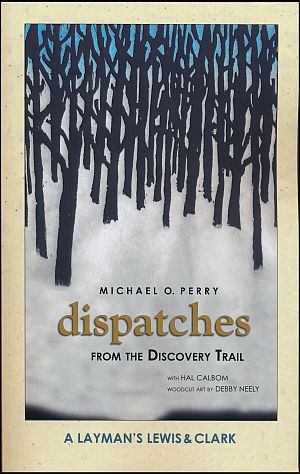

Michael Perry‘s excellent series on the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804-06 that first ran in the Columbia River Reader has now been published in one volume, Dispatches from the Discovery Trail: A Layman’s Lewis and Clark.

Mike discusses his multi-year research, reading the journals and following in the tracks of the Corps of Discovery.

About the book:

Beautifully illustrated by the Pacific Northwest woodcut artist Debby Neely and edited by Hal Calbom, the book is available at the Columbia River Reader office and at www.crreader.com/crrpress.

Alan: How did you come to write your series on the Lewis & Clark expedition?

Mike: After a trip to the beach in late 2003 with my sister and a friend, we sought shelter and a drink after digging only three clams. Sue told us she was thinking about buying a regional newspaper and asked if I’d write a monthly column about Lewis and Clark since the 200th anniversary of their trek was nearing. At first I wasn’t too enthused since my knowledge of the Corps of Discovery was quite limited. But, the more we talked, the more intrigued I became and agreed.

I think anyone living along the route the Corps of Discovery has a natural interest in what went on in their neck of the woods 215 years ago. Thus, I was particularly interested in their trip down and back up the Columbia River. While my intention was to cover everything along their route, my main goal was to flesh out as many details as I could find about this area.

However, when I bought my first reference book (Bernard DeVoto’s 1953 condensation of the Lewis and Clark journals) I was surprised to find just a couple pages devoted to their travel between Portland and the mouth of the Columbia. I felt there had to be more to the story. I looked at a copy of Stephen Ambrose’s “Undaunted Courage” and was even more disappointed.

So, I decided to go all in and bought a complete set of the Lewis and Clark journals. There are over a million words in those 13 volumes. But, I soon found myself hooked! Reading the original journal entries, I could imagine what they were going through each step of the way.

Alan: Was there a part of the expedition that most interested you?

Mike: I was lucky enough to have been given a copy of Rex Ziak’s amazing book “In Full View” for Christmas of 2003. Rex, who grew up and lives in the Naselle area, had spent a decade reading the journals, focusing on their time at the mouth of the Columbia. He retraced their steps, especially during the nasty winter months so he could better understand the impact of their words. Being able to retrace their steps and attempting to put myself in their shoes to imagine what they were going through was powerful.

The other part of the story I found myself attracted to was centered around Great Falls, Montana. Our son was going to college in Bozeman at the time, so when we went to visit him I’d plan an excursion to places the Corps had passed through. Even before I had read and written about their nearly disastrous trip across the Rocky Mountains, I had come to realize how difficult the trip had been. Most of their route across America is now gone, much of it flooded behind the many dams on the rivers they traveled. But, at Great Falls, they had to portage everything around five major waterfalls with a drop of over 600 feet… that 18-mile portage was grueling and is still unchanged.

Alan: The Lewis & Clark expedition has become so iconic in the nation’s imagination, were there any surprises for you as you researched the story?

Mike: The biggest surprise was how much help the Expedition received from Indian tribes. When the Corps reached the headwaters of the Missouri River in western Montana, they finally had to accept the fact there wasn’t going to be an easy all-water route to the Pacific Ocean. If it hadn’t been for the horses and help they received from the Shoshone Indians, it seems almost certain the Expedition would have failed to reach the west side of the Rocky Mountains. All the Indian tribes between there and the ocean were willing to provide food when the Corpsmen were starving.

Alan: Which of the two leaders were you most drawn to, and why?

Mike: Meriwether Lewis was the most difficult personality for me to figure out. Lewis was, without a doubt, a great leader and made excellent plans and preparations that led to a successful trip. However, most scholars believe he suffered from depression and/or some other form of mental illness. There were several long periods when Lewis didn’t write a single word in his journals. And, after the Expedition returned to St. Louis in 1806, his life seemed to spiral downhill, out of control. He was supposed to write a set of books about the trip, but in three years he never wrote a word. Finally, on his way to Washington, D.C. in 1809, he apparently committed suicide. As I read, and reread, his journal entries, I always tried to look a little deeper into what he might have been thinking at the time.

Alan: What is your writing process?

Mike: While I bought more than my share of books about Lewis and Clark, I read very few of them. Instead, I tended to read just one or two books to get an overview of what the bigger picture might have been that month, and then I turned to the actual journals to read with the intention of pulling out tidbits that I found interesting. I knew I couldn’t compete with the serious historians since I had a 1,000 word limit on each monthly column. My biggest fear was leaving something important out, or even worse, not getting the facts right. Thus, even though I had to focus on each month’s column, I also had to read ahead a couple months to be sure I set up the storyline for things to come.

Alan: Are you currently working on any other history projects?

Mike: Nothing concrete. After I finished the 33-month “Dispatches From the Discovery Trail” I began writing another series of monthly columns for the Columbia River Reader titled “Postmarks Along the Trail”. In those columns, I would try to focus on things people could do on simple day trips in the the Lower Columbia region. I wrote about dying towns and what they had been like 75 or 100 years ago. Some of my fondest stories involved taking backroads to those almost forgotten places. Most of them still have a cafe or hardware store to check out!

I love driving the so-called Blue Highways – the thin blue lines that mark the backroads on paper maps that, in some cases, were the main highways not too many years ago. One of my favorite quotes is by Charles Kuralt. At the end of one of his TV news segments, he said “Thanks to the Interstate Highway System, it is now possible to travel from coast to coast without seeing anything.” We can all benefit by slowing down and learning about the past

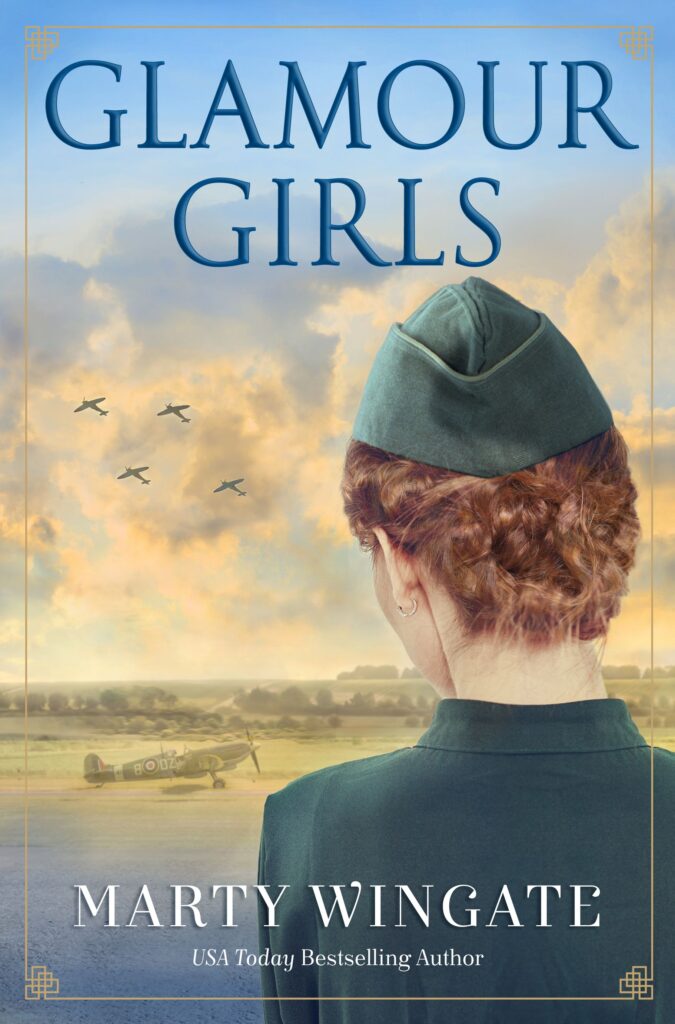

USA Today best-selling author Marty Wingate‘s latest book is the historical fiction novel Glamour Girls (Alcove Press), which follows Spitfire pilot Rosalie Wright through both the physical and emotional dangers of the Second World War. Marty also writes The First Edition Library series (Berkley) set in Bath, England, about the curator of a collection of books from the Golden Age of Mystery. In book two, Murder Is a Must, an exhibition manager is found dead at the bottom of a spiral staircase—a la Dorothy L. Sayers. Marty also writes the Potting Shed and Birds of a Feather mystery series.

About the book:

During World War II, farmer’s daughter Rosalie Wright becomes a pilot assisting the RAF. But will a romantic rivalry send her aerial dreams plummeting to earth?

Ever since she was 10 years old, Rosalie Wright’s eyes have been on the skies. But at the age of 18, on the verge of earning her pilot’s license, the English farmer’s daughter watches her dreams of becoming an aviatrix fly away without her. Britain’s entry into World War II brings civilian aviation to a standstill. Then, Rosalie’s father dies, leaving her, her mother, and her brothers to run the farm.

Everything changes when she learns that the Air Transport Authority is recruiting women pilots to ferry warplanes across Britain to RAF bases. Despite her mother’s objections, Rosalie cannot resist the call of her country–and the lure of the skies. During her training on Gipsy Moth aircraft, Rosalie forms a fast friendship with fellow flyer Caroline Andrews. Her trusty Ferry Pilots Notebook by her side, Rosalie delivers to five airfields in a day–while fighting an endless battle against skeptical male pilots and ground crews.

She would much rather spend her time on the wing than on the arm of any man…until she meets gruff pilot Snug Durrant and RAF squadron leader Alan Chersey. Snug is a cynical, wisecracking playboy, and Alan is every WAAF’s heartthrob…and Rosalie catches both their eyes. As the war drags on, and casualties mount, will love and tragedy send Rosalie’s exhilarating airborne life crashing to the ground?

Alan: You are a very successful mystery writer. How did you decide to branch out into historical fiction with Glamour Girls?

Marty: I’ve always enjoyed the historical research I’ve done for my mysteries – all of which are set in Britain – so it wasn’t a far reach to decide to write a WW2-erabook. I wanted the story to stand alone and not be part of the mystery series, with new characters that live within only this one book.

Alan: How did you come up with the story? Is it based on an actual person?

Marty: Yes, my main character Rosalie Wright was inspired by Mary Wilkins Ellis, one of the women ferry pilots of the Air Transport Auxiliary who flew Spitfires and many other sorts of planes around Britain, delivering them to RAF bases. Mary died in 2018 at age 101! I read her autobiography and the stories of other pilots and picked and chose what I wanted to weave into Glamour Girls.

Alan: Did you find the process of writing a historical novel different from the process you use to write your mysteries? If so, in what ways?

Marty: Lots more research, which is both fun and worrying, because it’s so easy to spend an entire afternoon reading the Christmas 1942 issue of Radio Times (digitized online) rather than write! To avoid this, I type XXX every time I come across something I should look up later. The trick is to remember to search the manuscript so I don’t leave any of those behind.

Alan: What is your usual writing process?

Marty: I write best in the morning, usually about two hours. I can edit later in the day, but I don’t often write a lot of new stuff in the afternoon. To begin with, I may have a description of the story and even a synopsis, but I don’t use an outline, and I write one draft. I write new stuff, and the next day go over that and write further, and the next day go over that and write further. It means I need to read over the last half of the manuscript one more time more than the first half, but it’s a process that works well for me.

Alan: How did you first get published? Did you use an agent?

Marty: Yes, I have an agent. I’m easily distracted, and if I had to do everything my agent and my publisher do, I would never get anything written. My first fiction, The Garden Plot, was published by Alibi, a digital-only imprint of Random House (now Penguin Random House). I had fabulous editors! I am now delighted to be in print as well as digital for the newest mystery series (the First Edition Library mysteries) and my historical fiction.

Alan: What project are you working on now?

Marty: I’m working on another historical novel set in 1957 England in a small town on the Suffolk coast. Book eight of The Potting Shed mysteries is (at last!) finished and will see the light of day one way or another. And, I’m also continuing the First Edition Library mysteries (Murder Is a Must, out in December 2020) and book three, out next January, features elements of Daphne du Maurier’s Frenchman’s Creek.

>>Watch Marty read at the February 9, 2021 WordFest on Zoom.