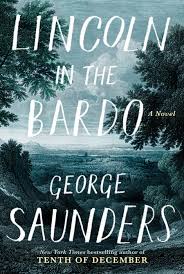

George Saunders

Random House

|

We embraced the boy at the door of his white stone home. from Lincoln in the Bardo |

Trapped in the limbo of his grief.

On February 20, 1862, William Wallace Lincoln died in the White House of typhoid fever. “Willie” was eleven years old, and President Abraham Lincoln was shattered by the death of his favorite son (“He was the kind of child people imagine their children will be, before they have children.”) Willie’s small casket was entombed in Georgetown’s Oak Hill cemetery

There were reports in some newspapers that Lincoln was seen returning alone late at night to the crypt, opening the coffin on these occasions to hold his son’s body once again. From these possibly apocryphal accounts, celebrated short story writer George Saunders (Tenth of December) has written his first novel.

In Tibetan Buddhism, the bardo is the state of transition from death to rebirth when the spirit of the deceased is in a kind of limbo before moving on to…wherever deceased spirits move on. Saunders populates the Oak Hill cemetery with departed spirits who for various reasons haven’t departed. (Apparently, the denial of death persists even after one’s died.)

Garrulous, argumentative, petty and noble, these spirits recount their former lives in ways reminiscent of Thornton Wilder’s play “Our Town” and Edgar Lee Masters’s Spoon River Anthology. Some stories are funny—the self-declared genius, still bitter because he wasn’t recognized as “the greatest mind of his generation”—while some stories are heartbreaking, such as that of the pretty mulatto slave who had been raped and abused ever since she was a young girl by her master and her master’s sons, by the overseer and pretty much any white man who felt the urge.

Two of these in-limbo spirits, Hans Vollman and Roger Bevins III, take a particular interest in Willie, wanting to help him on his way since it’s especially not safe for children in the bardo state. (“The young are not meant to tarry.”)

Their kindly efforts to help the boy move on are frustrated by the surprising and secret night visits of the grieving president to the boy’s crypt. Understandably, Willie is reluctant to leave this place, desiring to see his father again and to feel his touch. Aided by several other helpful and not so helpful spirits, Vollman and Bevins must use their supernatural influence on the president to overcome his grief and release his son so Willie’s spirit will be free.

The resulting story is at times deeply moving, at times very funny, at times confusing, altogether an amazing and original work of imagination from a master of the short story.

This review first appeared in The Columbia River Reader (April 15, 2017-May 14, 2017.) Reprinted with permission.